There is a wonderful concept in Hebrew known as Shmita, or “year of release.”

It refers to a sabbatical taken every seventh year, rooted in the traditions of ancient Israel, during which the land is left to lie fallow. Based on agricultural wisdom, the soil is given a full year to rest—not cultivated, not harvested, simply released to its own will.

While few of us can afford a year of literal sabbath, the spirit of Shmita can be honoured in small ways—anytime we choose rest and release over grasping.

For that year, the farmer enters a long-form meditation on reversal: as much as she may work to control the soil, she recognises that the land owns her—not the other way around. It is the provider that nourishes, shelters, and sustains her.

The Illusion of Control

In a Shmita, we are invited to ask: how much control can we yield? Where can we allow ourselves to be carried?

Though we imagine ourselves to be in charge of our lives, we are at best participants in a momentum of cosmic scale. Especially now, in this age of environmental and social collapse, many of us feel an existential anxiety that stirs an urgency to attend to things—before it’s too late.

We soothe ourselves with stable routines, familiar activities, and pleasantly decorated shelters. We move within a limited, manageable radius to mitigate the unexpected.

At heart, the whole human drama is like an elaborate bid for permanence, played out on a rapidly spinning, shifting planet. Even our language is corralled into databases, as if the perfect words might secure us as we’re hurtling through space.

And yet, the more we grasp for control, the more turmoil erupts. We see this clearly in systems of rigidity—whether social, economic, political—where attempts to impose order on a grand scale often ends in division and chaos.

So is it true in our individual lives. While the impulse to control can be helpful in moderating our sudden urges and behaviours, it also has a shadow side that, when left unchecked, can colonize the rhythms of daily life.

It shows up in our overstructured days, our curated selves, micromanaged health routines, compulsive news-scrolling, and so on. These forms of personal rigidity also breed chaos, manifesting as burnout, addiction, insomnia, depression, and displaced anger. Like trying to hold a beach ball under water, what we try to contain eventually erupts.

The Wisdom of Seasons

Control is one of the great pillars of rationalism, our 400-year-old project to better understand, predict, and ultimately command the world. We want our crops in tidy rows, producing endlessly and delivering exponential gains. But this is not the way of nature. Nature is cyclical—by turns expanding and contracting, giving and withdrawing, nourishing and depriving, living and dying.

If we really want to live in cooperation with Earth’s rhythms, we must become equally curious about her fallow seasons. And our own. Shmita asks us to stop forcing the soil long enough to notice what unexpected gifts sprout of their own volition from the ground of the imagination.

But if we are so accustomed to having our hand in everything, how do we learn to let go?

Sacrifice is Sacred Pruning

I’ve always marveled at the word sacrifice, which comes from the Latin sacer (sacred) and facere (make)—to make sacred. Hidden in the word is a kind of ancient technology, a clue to its deeper function.

In myth, there is always a moment when the hero or heroine must cross a threshold into the unknown. To do so, they’re asked to relinquish something of value, often something they’ve become entangled with. Even if that attachment once brought comfort, like Siddhartha walking away from the gilded security of the palace.

That relinquishment sets a transfer of power in motion. In naming and releasing what has kept us tethered, the energy once bound in control is set free in the soul. Like a fountain of generosity, it becomes a wellspring of renewal from which we can draw. In that opening, something mythic begins to stir. An invitation to live in deeper accord with the Way that moves beneath our schedules and plans.

Shmita invites us to step outside of time—to renounce the ego’s urgency for progress, for the real possibility of being breathed, being danced, being sung into the greater song of things.

Sacrifice is the first gesture of trust in the unknown. It is the pruning that redirects your energy toward your next becoming. Like quitting a stifling job only to have something unexpected and luminous appear that same afternoon. There is magic in sacrifice.

Life is calling you forward, and your severance of the tethers that bind you to outgrown forms is the answering of that call. Your willingness to step into the emptiness from which all life springs is a gesture of devotion to your own belonging.

Paradoxically, pruning doesn’t leave us impoverished. Generosity becomes the natural overflow of a life pared back to its essence. It awakens an instinct to offer something back to the mystery that sustains us.

Around the world, many cultures practice a miniature, daily form of Shmita through the act of offering. Even in times of scarcity, they make gifts to the holy in nature: a handful of rice, a bowl of fruit, a garland of flowers, prayers carried up to the heavens on a wisp of incense.

Feeding the holy is a gesture of recognising our indebtedness to what makes our generosity possible in the first place.

The Fertility of Ambiguity

Once the field has been cleared, a kind of temenos is created: a sacred, protected enclosure where something new can be invited. In the absence of our usual structures and compulsions, we gain the rare chance to experiment with unfamiliar orientations, to welcome new influences, and to try on diverse ways of being.

As a counterpoint to the monocrop, the monopoly, the monocrat, diversity is essential to creativity. This is true in nature, culture, and consciousness itself.

Welcoming ambiguity into our own world is like introducing chaos in its most benign form. Think of it as a homeopathic dose of uncertainty. Rather than being side-swiped by disorder when control fails, we begin to tolerate small servings of the unknown. We practice holding the tension of multiple perspectives at once. Like compost folded into familiar soil, ambiguity enriches the landscape of our lives. It loosens rigidity, nourishes new growth, and teaches us to trust what we cannot yet reconcile.

How often do we become so attached to our way of thinking that it grows into a hedge—cutting us off from others, and from the wilder parts of ourselves? That’s the paradox of hedging: it protects, but it also isolates. Without cross-pollination, our inner landscape grows brittle. We need rogue ideas, unfamiliar companions, and unexpected nutrients to shift our habits, reveal blind spots, and awaken dormant gifts.

Ambiguity, when welcomed, is not a threat to order—it’s the loamy humus of transformation.

Rewilding the Imagination

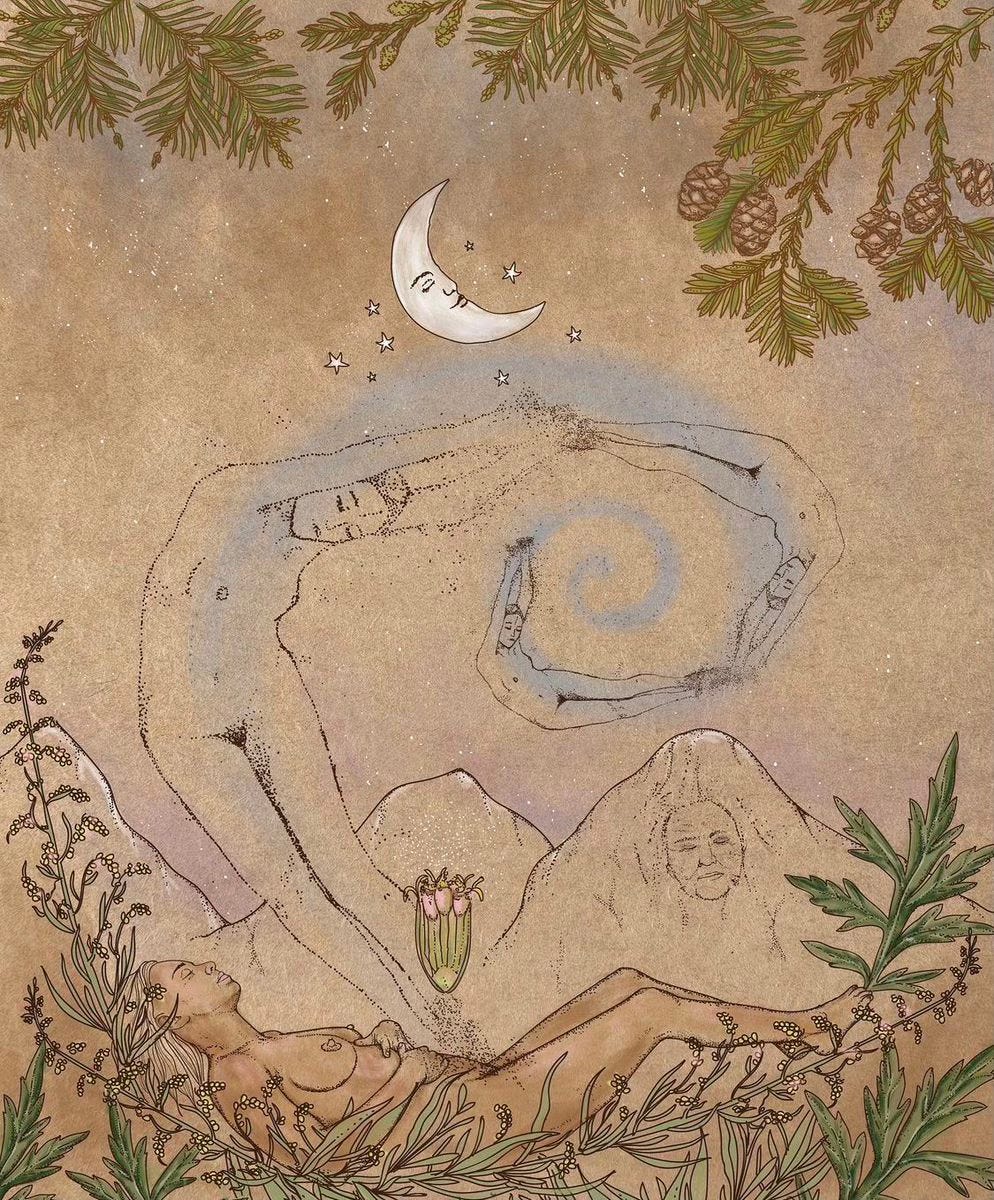

The Shmita is a year devoted to letting the land of our lives be at rest. Not in the sense of passivity, but rather a deliberate surrendering to those deeper currents that are pulling us into life’s joyful and messy momentum.

This kind of rest is a form of rebellion, one that reorients the very criteria guiding our choices. It is a conscious refusal of the mainstream feeds and inputs: those “controlled substances” we call social media, the news cycle, the aggressive linearity of calendars and to-do lists, the performance of self we’ve constructed to stay legible to others.

Shmita invites us to step off the moving sidewalk. To let the noise of consensus reality recede long enough that something quieter, older, and wilder might make itself heard, like colourful weeds growing through the rubble.

Rewilding the imagination begins in the body. It starts in the simple and sensual pleasures of being alive. Mornings spent recording your dreams, a steamy coffee within reach. Afternoons in fragrant breezes, fruits of the season elevated to high art on your dinner plate. It begins with the decision to not have a goal. Like walking unplugged through nature, or taking an unfamiliar route just to see where it might lead you.

Adorning the Emptiness

The magic of the Shmita is kindled in structured-unstructured time. Even if that time is only an hour or two, its boundaries are fortified. Your mind can feel safe enough to wander, and your body to follow, because no one—not even you—is expecting an outcome.

I call this adorning the emptiness. It’s like preparing your home for an unknown guest: clearing a space for them to rest, filling the pantry, placing beautiful things within reach. Only the guest is not a person, but the estranged aspects of your being.

This is the practice of inner hospitality: making room for joy and generosity to be lured out of hiding. And as you circle the questions on your heart, you relinquish your hope of solving them, in favour of the humble aim of asking more artfully. Without the pressure to commodify what you find there, your creative juices are free to bubble and ferment below the surface.

Something Amazing is About to Happen

It’s tempting to see the Shmita as a form of retreat from life, but it’s actually a deeper involvement with it. By refusing urgency, we have a chance at restoring our natural rhythm, which is attuned to the tempo of the biosphere.

A friend once shared a dream about a relationship escalating toward conflict. In the middle of it, she found herself saying: “Something amazing is about to happen.”

I love this mantra for the Shmita. Expecting something amazing is the perfect posture for this kind of time. It reminds us that we stimulate vitality by putting ourselves in the way of change. That beyond the complete cessation of habitual patterns lies the excitement of life itself.

This summer, I’ll be entering into my own micro-Shmita.

From July through part of September, I’ll be clearing my schedule of external commitments and stepping back from regular output, including here on Substack.

I don’t yet know what, if anything, will emerge. But that’s more or less the point! I’ll be resting the land of my life. Resisting the impulse to fill, to explain, to harvest too soon. I’ll be taking some risks, walking new routes, setting beautiful things within my reach.

I may share the occasional fieldnote from within the experiment. Or I may go quiet for a while. Either way, I’m not disappearing, but just leaving a space for something amazing to happen.

For those of you with paid subscriptions: thank you for making this kind of rest possible. Your support allows me to live what I teach, even in the quiet seasons. If you'd prefer to pause your subscription during this time, I completely understand and support that, too.

If you’re feeling the pull to enter your own kind of Shmita—however small—I’d love to hear about it.

I love this and feel so inspired to have this name/word/intentionality behind what I’ve been playing with and feeling called to have more “unhedged” time. The pattern of what happens when we have a too tight pen/fence for our ideas, time, actions and flow is alive and I love this concept of Shmita as being able to cross pollinate the mystery with potential and form.

I love this so much! I have been circling around this idea but you made it concrete. Thank you so much for sharing your beautiful words and ideas and best wishes for your Shmita 🌞